New direction for an old collection

Making the Victorian Parliament’s heritage collection more accessible to the community is an important goal of the team that manages it.

If you’ve ever toured Victoria’s Parliament House, you’ve probably already caught a glimpse of the handful of artefacts on display in its library.

But a beige room a short walk away is home to thousands more relics of Victoria’s history.

Inside, there is a shelf for a single pair of patent black leather shoes, a series of horse-hair wigs and a gold medallion that once entitled members of parliament to unlimited free railway trips around Melbourne.

There are also parliamentary dinner services and a framed letter of thanks to the state of Victoria from Prince Alfred (the son of Queen Victoria) who survived an attempted assassination during his visit to Sydney in 1867.

Only a handful of parliamentary staff have security clearance to enter the room, which is climate-controlled to protect these and all of the roughly 25,000 photographs, archives, rare books, paintings, sculptures and other items in the parliamentary heritage collection.

Two of those staff are the collection’s custodians, Sarah Edwards and Emma O’Connell. The pair, who have backgrounds in museum curation and art history, have been assigned to take carriage of the collection and to maintain the building’s living history.

Ms O’Connell acknowledges that the range of the collection is very broad, but insists that every item tells a story about the state’s history.

'We ask ourselves is this significant to parliament in any way? Is it significant to the building, to a person within parliament, to an event that’s taken place here?' she says.

'Unlike a gallery or a museum which displays what you’d expect, there are all sorts of things in our collection. That’s what makes it so wonderfully unique.'

There are also the practicalities of maintaining an ever-growing collection. With limited space to store pieces donated by parliamentary staff and members of the public, they must also consider their value in other ways. Could they ever find a home in a public exhibition elsewhere? Does parliament have the resources to conserve them over time if they were kept?

Ms O’Connell says the collection is also strictly apolitical to ensure it is not bound to any party’s version of history. Instead, the items must say something about the life of the Victorian Parliament itself. It includes, for example, thirty three-pence coins which the Member for Prahran threw over the Member for Carlton in the upper house in 1955 as he called him a 'Judas' for defecting from the Labor party.

“ The collection is a way of providing some interesting, valuable and historic links back to community so people feel more engaged with what we’re doing, and what parliament is all about. ”

Sarah Edwards

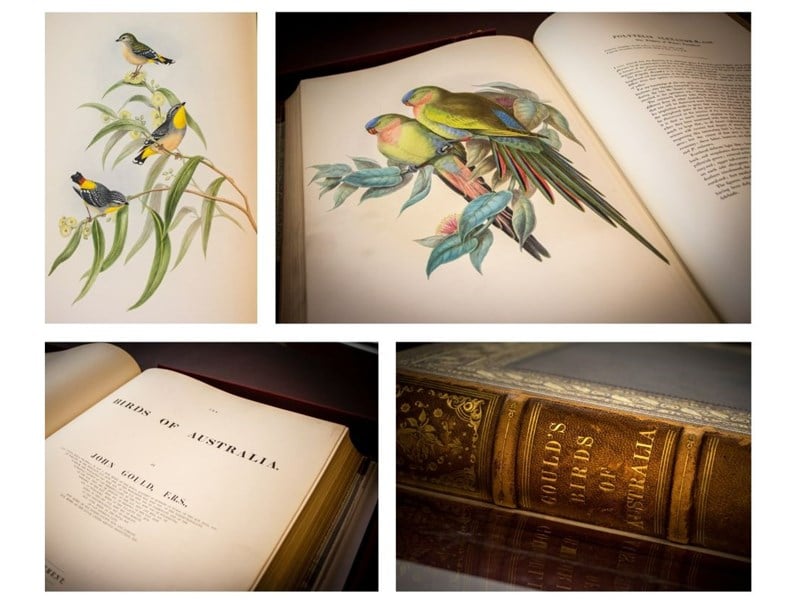

Ms Edwards’ favourite item in the heritage collection is a series of rare books called Birds of Australia by John Gould. Each volume is so large and so heavy it requires two people to take it down from its shelf.

Ms Edwards, who formerly worked in the natural science collections at Museums Victoria, carefully turns each page, which has been hand-sewn into the book’s fraying spine: 'It’s a great treat, I don’t get to look into this often,' she says.

Gould, an English businessman, came to Australia with his wife Elizabeth in 1838. They left their children behind for two years for their latest business venture - a series of illustrated bird encyclopaedias that they would publish and sell on-demand. At two-hundred and fifty subscribers it was a raging success.

Gould hunted and taxidermied the birds, which were then lithographed and hand coloured on the page in painstaking detail by a number of artists including Elizabeth, providing England its first glimpse at the wildlife in the new colony.

By contrast, Ms O’Connell’s favourite piece is arguably the smallest book in the parliamentary heritage collection.

It’s a pocket-sized sketchbook, filled with pencilled drawings, and belonged to artist William Strutt, who came to Australia in the 1850s at the age of 24. Much like Gould, Strutt was seeking to make a name for himself, but he wanted to secure wealthy Australian clients who would commission him to paint for them.

Strutt later became famous for Victoria the Golden, an album containing his drawings from his travels around Victoria. Inside were various scenes of daily colonial life, as it was then. Women chopping wood while their husbands went to the goldfields (‘Women left behind’). Indigenous police officers, then known as ‘Native Police’ resplendent in formal uniforms. Wills’ imagined embrace of Burke as he lay dying.

Though Strutt eventually returned to England, Victorian Premier Thomas Bent travelled to London to buy the album from him years later, along with one of his sketchbooks.

Ms O’Connell says that it’s the immediacy of his early sketches, complete with notes for the colour and the material of the clothing that the people he observed wore as he put pencil to paper, that excite her, even more than his completed paintings.

'I think that’s why I love this one so much,' she says of the sketchbook. 'It’s a real insight into Strutt’s mind, capturing the moment right then,' she says.

The early parliamentary librarians were tasked with building a collection of prized books to publicise the new colony of Victoria, Ms Edwards says.

'At the time Melbourne wanted to attract people here who were not just about gold. They were also wanting to attract the intelligentsia and people who had broader, more intellectual pursuits,' she says.

While the Parliamentary Library predominantly remains restricted to members and former members of parliament, in the late 1800s it was used for more than research. Then commonly known as a ‘gentleman’s library’ it was filled with books like Gould’s Birds of Australia - books about natural science, the early explorers and even poetry, many of which remain in the heritage collection.

And while today Parliament, like its library, is more a place for political business than leisure, the heritage officers say they are here to curate the building’s living history. That means preserving its history from the state’s earliest days to choosing what furniture, paintings and other mementoes to keep from the present day for future generations. And their audience is no longer the world outside of Australia but the local community.

'We’re very aware that this collection belongs to the people of Victoria,' Ms O’Connell says.

She says they want to make the collection as accessible as possible, and now regularly loan items to the National Gallery of Victoria and the State Library for relevant public exhibitions.

Although historically such items were cared for 'under lock and key', she says: 'Now we really try where we can to get it out there.'

Both heritage officers say they hope there will one day be a bigger space in Parliament House to showcase more of the collection to the public.

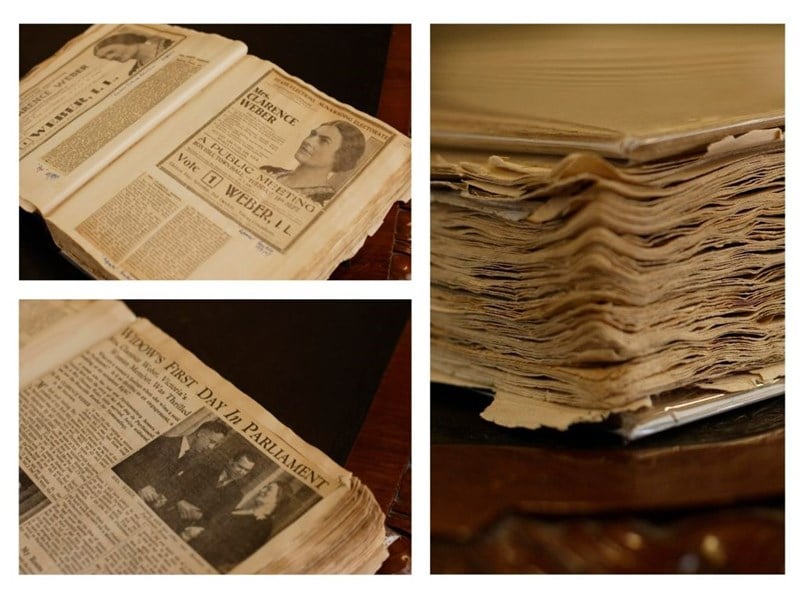

Ms Edwards says she also wants to use the collection to better highlight the contribution women and First Peoples have played in the history of parliament.

'In the past Parliament has been an exclusive, male-dominated club. The collection is a way of providing some interesting, valuable and historic links back to community so people feel more engaged with what we’re doing, and what parliament is all about.'