The story behind the story

High-tech Hansard opens the digital doors to democracy.

It’s just a little red light but when the Premier stands in Victoria’s Parliament and begins to speak, a tiny bulb on an unobtrusive microphone signals that, behind democracy’s pomp, polished timber and padded leather, a high-tech operation is underway.

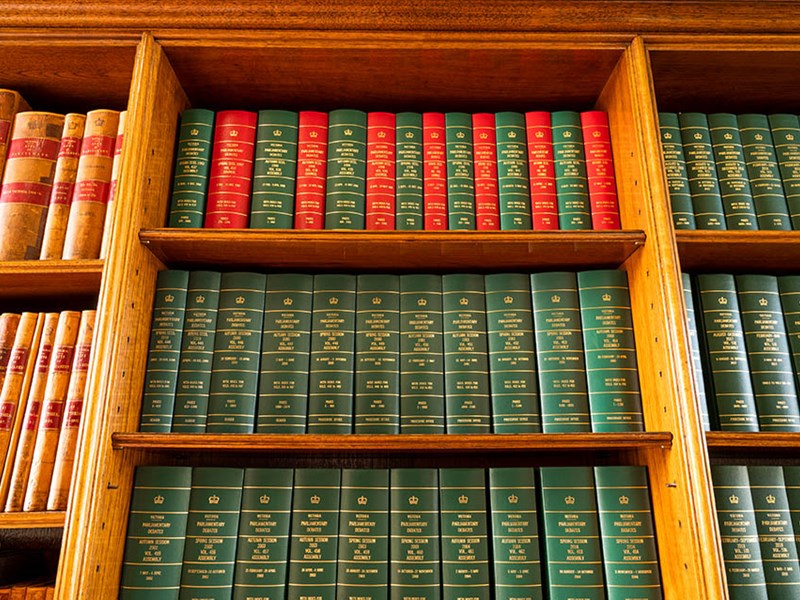

This is Hansard. A single word for a service that’s recorded millions of them in 153 years of commitment to the parliamentary record. In creaking 19th century offices beneath the parliamentary chambers, a multiplatform content powerhouse to rival mainstream media pumps out text and images via web streaming, social media, on-demand video, broadcast television and, of course, the red and green bound volumes beloved of MPs for their office bookshelves.

For 120 years after the first official Hansard reports in 1866, Parliament’s technology barely advanced beyond fountain pens and typewriters. Where once shorthand notetakers and stenographers with their mysterious machines bore witness, Hansard is now recorded on auto-activated microphones and cameras feeding Cloud servers, web streams and broadcast feeds. Reporters and editors rely on voice-recognition programs to publish reports online and in print within hours instead of days.

Hansard gives Victorians more access than ever to their politicians and parliamentary proceedings. Members, as well as enjoying more digital paths to their constituents, benefit from a suite of tech developments and improvements, including video streaming of proceedings to their offices so they can monitor debates — and never miss a vote — and user-friendly connectivity in committee and meeting rooms to accommodate different devices and facilitate presentations and video conferencing — all thanks to Hansard’s AV section.

Throwing open digital doors to the public also meant rethinking a core Hansard mission: to be an accurate, but not verbatim, report. From day one, Hansard committed to presenting members in their best light, correcting their grammatical missteps, mangled metaphors and mistakes for the written record. Hansard, Victorian founder William Robinson once told a new MP, was meant to 'preserve the idiom of Parliament, not the idiots'.

Now, technology offers little cover for fools. 'And that’s a good thing,' says MP Jacinta Allan.

'We can request clips of our speeches and put them up on social media to show the world what we’re doing, so on that level Hansard technology is great,' Ms Allan says. 'It’s making Parliament more visible to the rest the world. But from time to time it shows that we need to be very conscious of how we behave.'

She remembers an incident involving a former member who, during a heated lower house debate in 2012, made an 'inappropriate gesture' while shouting across the Lower House. The member denied any wrongdoing and the Speaker was forced to release Hansard’s video, which showed there was indeed an unparliamentary moment. The gesture and Hansard’s footage of it went around the world.

But Hansard’s evolution in capturing the colour and movement of Parliament is not all about bad behaviour, says Ms Allan. While Hansard texts 'can be very kind to us, smoothing out the stumbles and bumps', the audiovisual technology also preserves moments of emotion, generosity, celebration and condolence on sitting days. 'Debates in the Parliament should be spirited where appropriate, they should be sombre where appropriate and that’s what makes Hansard’s role really special and important, capturing those moments for the historical record forever,' she says.

Senior Hansard staff agree. Many talk about important debates that brought out the best in members of both houses and Hansard staff on the front line of history.

These include the assisted dying debate that ran for about 100 hours over a sitting week in October 2017, including a 28-hour final session that left members (and Hansard staff - the debate took up 174 printed pages) exhausted and tearful.

Or the highly charged 2008 debate over decriminalising abortion, which elicited implacable views — and 40 amendments - from members and the public gallery. Media quoted Council President Bob Smith shouting at security guards to haul out protesters as the bill passed: 'For God's sake do your job… Amateur hour up here.'

'Vote 23-17 in support of motion', Hansard records drily. 'Interjections from gallery. Persons escorted from gallery.'

Veteran Hansard editor Trish Greig cites the 2012-13 parliamentary inquiry into institutional child sex abuse as another challenging but ultimately rewarding time for Hansard staff.

'Giving people a voice, that’s what is so important, and doing it in a professional and pure way,' she says, 'I like being part of a democracy where we provide people with that opportunity.'

“ It’s making Parliament more visible to the rest the world. But from time to time it shows that we need to be very conscious of how we behave. ”

Jacinta Allan

So how does Hansard work? Something like this:

A member gets to her feet, starts her speech with 'Thank you, Speaker' and the instant light on her microphone indicates she is live and the focus of the chamber’s automated high-definition cameras. At the same time metadata including the member’s name and electorate are feeding into recording servers and the broadcast feed. Meanwhile, a Hansard reporter starting his 'turn' at a desk in the chamber takes down details like the time, subject matter, who’s interjecting and any change in the Speaker’s chair.

The member appears on a wall of screens in one of three control rooms in the Hansard broadcasting unit, where three operators switch vision between the six cameras, add graphics and monitor the live stream to the media room and parliamentary website.

Back in the House, the reporter ends his turn, slips out of the chamber and, at his desk, starts ‘speaking in’ the recording using voice-activated transcription. This means replaying proceedings through headphones and repeating them to his computer, which recognises his voice and quickly formats text with the help of customised commands and a vocabulary of titles, common words, terms and jargon.

The reporter saves the text as a Word document and, in another room, a sub-editor picks it up and checks the audio, facts, style, headings, titles. If all is correct, the report is fit to go online and as the latest printed instalment in a ‘progressive publishing’ process.

Awaiting publication, the member approaches Hansard’s ‘concierge service’ and asks for a video clip of her speech to post on social media, and a print copy. She’ll have both within three hours.

Overseeing this process are two editors, one each for the Legislative Assembly and the Legislative Council.

'Members still like their printed extracts but more and more it’s swinging towards video,' says Foong Ling Kong, long-time Hansard staffer and Assembly editor.

'The requests for video on demand have gone up exponentially since the service was first offered... and of course that’s because of social media.'

What’s next for Hansard? Audiovisual supervisor Angelo Altair sees video driving near-future change like closed captioning for the hearing impaired and video-on-demand for the public.

Further down the track, Angelo, who has been involved in every Hansard tech development since the mind 1990s, predicts heads-up screens for members in both houses. 'That would be very helpful from a broadcast point of view,' he says, 'because a lot of the time members are looking down, reading notes off their desks, so all you get is a shot of the tops of their heads.'

Screens are already essential to members and Foong Ling Kong is a fan.

'You can see technology creeping into the chamber, with more people reading from iPads and their phones instead of pieces of paper. That’s a big change,' she says.

'One of the most powerful images I have in my head is of Lidia Thorpe, the former member for Northcote. When she gave her inaugural speech she was wearing a possum skin cloak and reading off an iPad. Sixty thousand years of heritage, reading off an iPad. And that was a wonderful image, that confluence of old and new, and that’s what Parliament does, brings them together.'

About the Author

Craig Dixon

Craig is a journalist who has previously worked as a senior editor for The Age.

This article was first published in August 2019.