- Home /

- News /

- Infrastructure

Drivers need to change to protect most vulnerable

7 May 2024

Two out of every five lives lost on Victorian roads so far in 2024 have been of those who have little or no protection in the event of an accident on roads, footpaths and driveways.

Vulnerable road users include pedestrians, bike riders, motorcyclists, the frail and elderly, people in wheelchairs and people with disability or relying on mobility devices.

A report tabled in the Legislative Assembly last week has recommended the Victorian Government take measures to prioritise the safety of vulnerable road users by adopting a ‘road user hierarchy’ where road users who can do the most harm to others have a duty of care to reduce the danger they pose to more vulnerable road users.

That would overturn what Deakin University researchers told the Committee was the usual ‘Australian social norm’, that ‘pedestrians and cyclists have a high duty of care to protect themselves’.

‘Australian roads have traditionally been designed for the convenience of drivers and motor vehicles, at the expense of vulnerable road users’ safety,’ the report says.

‘This has created a culture where pedestrians, bike riders and motorcyclists among others are seen as less legitimate users of the road. Cars, vans, trucks and buses provide their occupants the most protection and can also cause the greatest harm in the event of a crash,’ it adds.

“ The Committee heard also about the worsening of behaviours, in particular that drivers are showing more aggression, they are distracted, they are impatient and they are engaging in risky behaviour. ”

Alison Marchant, Committee Chair

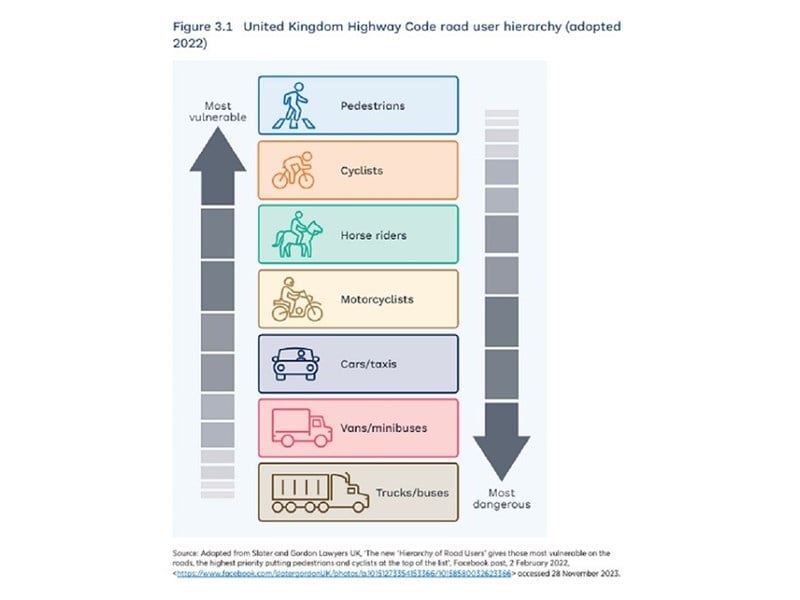

The ‘road user hierarchy’ approach was recently adopted by the United Kingdom to help create a cultural shift, whereby road users who can do the greatest harm to others understand the onus is on them to reduce the risk they pose to others.

This puts those most at risk in the event of a crash at the top of the hierarchy, placing pedestrians first, followed by bike riders, horse riders, motorcyclists, cars, vans and minibuses and finally heavy vehicles, such as trucks and large buses.

The inquiry found that, while there is a lack of published supportive data, anecdotal evidence suggests Victorian drivers’ behaviour deteriorated during and after the COVID‑19 pandemic.

‘The Committee heard also about the worsening of behaviours, in particular that drivers are showing more aggression, they are distracted, they are impatient and they are engaging in risky behaviour,’ Committee Chair Alison Marchant told the Legislative Assembly.

‘Some of that risky behaviour is intentionally running red lights, using a mobile device and, unfathomably, not wearing a seatbelt when driving,’ she said.

The report has 61 findings and makes 56 recommendations.

While the report makes recommendations aimed at increasing the awareness of drivers about vulnerable road users, it also acknowledges that behaviour change is difficult to achieve.

‘Awareness is important but complementary approaches are needed to change behaviour and protect vulnerable road users such as enforcement and infrastructure that separates vulnerable road users from motor vehicles and that guides motorists to slow down in areas with high volumes of bike riders and pedestrians,’ the report says.

It recommends the Victorian Government place greater emphasis on the safety of vulnerable road users in future road and urban infrastructure design and strategies.

The Committee makes a range of other recommendations including; creating a vulnerable road users’ advisory group to contribute to the development of road safety interventions; reviewing the flexibility of speed zoning guidelines with the aim to decrease suburban ‘rat running’; reviewing the location of pedestrian crossings on arterial roads to ensure there are regular crossings linked to public transport stops, activity centres and schools; prioritising road treatments in regional areas and running a targeted campaign on regional road safety to improve safety for vulnerable road users and encourage safer behaviours on regional roads.

The Committee received more than 300 submissions and held six days of hearings. The Victorian Government is required to respond to the Committee’s recommendations within six months.

The final report is available to download from the Committee’s website.