The father and son who sculpted Parliament House

In early 1888, just as now, much of the front of Parliament House was enclosed in scaffolding. In March of that year The Age ran a story anticipating the wrapping would be off the building by Christmas of 1889. Inside, in Queen’s Hall, sat the models, sketches and scale renderings produced by the skilled sculptors, artists and stonemasons competing for the highly sought prize of decorating the most significant building in the colony.

The Age article went on to promise that on 'the steps a couple of bronze lions, each 12 feet in length, will be placed, and at different points on the front parapet, 70 feet above the bluestone base.'

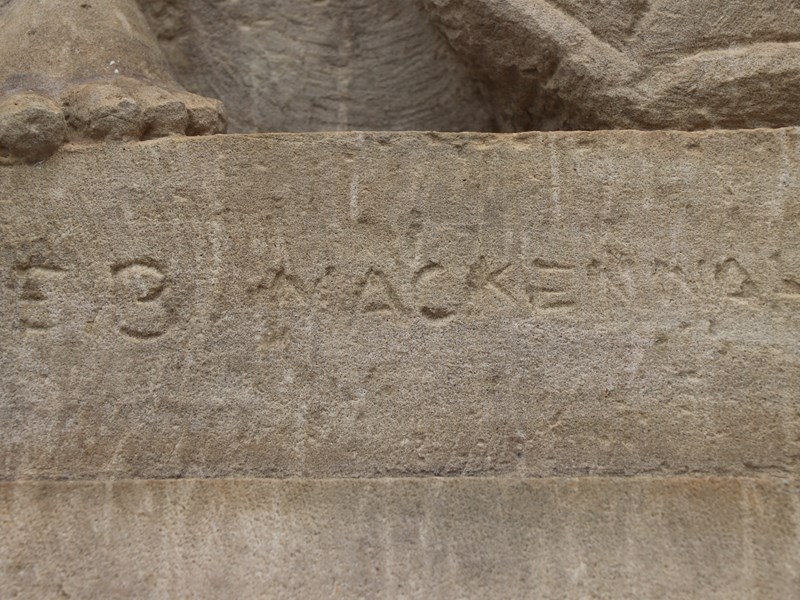

The lions were part of the vision of Parliament architect Peter Kerr and his desire to provide the building with symbolic protection against bad influences. But, while prominent sculptor John Mackennal won the commission, the lions never happened. The 1890s depression intervened and all we have to show is a quarter size plaster maquette that, these days, is held under glass in the Parliamentary Library.

But the decorative bas-relief sculptures proved depression proof. Also propped in Queen’s Hall in 1888, awaiting approval by the building commission, were models for the two relief sculptures designed for the front of the building. These were the work of Bertram Mackennal, the son of John, who would go on to become one of Australia’s most celebrated sculptors.

More than 130 years later they have now been repaired and restored by the skilled stonemasons working on Parliament House today.

The ambitious young Bertram Mackennal was working as the head of modelling and design at the Coalport Potteries in Shropshire, when he was invited to enter the closed competition. He won with his allegorical designs depicting art, commerce, industry and agriculture and returned to Australia in 1887 to complete his first public sculpture commission.

Mark Holsworth, author of Sculptures of Melbourne, recounts how in the 'late-nineteenth and early twentieth century working class stonemasons could see their sons become upper class gentlemen sculptors.'

That was certainly the trajectory that Bertram Mackennal was on. He opened a studio in Swanston Street and won several other commissions, but without enough clientele to maintain a steady stream of work, he left for Paris in 1891.

After a period of struggle, he finally made his name at the 1894 Royal Academy summer exhibition with a life size sculpture ‘Circe’. For nearly forty years he thrived under royal patronage, designing the medals for the 1908 London Olympics, Westminster’s parliamentary war memorial and exhibiting at the Royal Academy and Paris Salon. He was said to be one of the few artists that King George V actually liked and he was awarded a knighthood in 1921.

These days, as well as the reliefs at Parliament House, his statues of Queen Elizabeth and King George can be found in cities as diverse as Ballarat and New Delhi and his sculptures are in the collection of galleries around the world, including the Tate in London and, of course, the National Gallery of Victoria here in Melbourne.